Last Monday was Memorial Day, which Heather and I acknowledged by visiting the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg on our way out for a quick visit to Madroño Ranch.

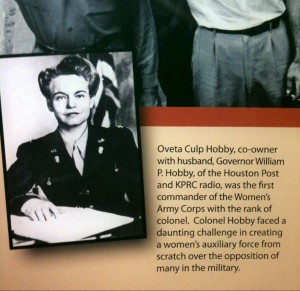

If you haven’t been there yet, I can tell you that the museum is an amazing place, crammed full of artifacts and information; we had no idea! (Those of you wondering why a museum commemorating the Pacific war is in landlocked Fredericksburg should know that it is the home town of Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet during World War II.) We were wandering through, overwhelmed by the number and detail of the exhibits, when we came upon a photograph (above) of Heather’s grandmother, Oveta Culp Hobby, who was the head of the Women’s Army Corps during World War II.

Mamaw, as she was known in the family, was a formidable woman. Born in Killeen in 1905, she was a proto-feminist (though I suspect she would be horrified to be described as such), both genteel and steely. Family legend holds that she displayed a strong sense of integrity, not to say stubbornness, at an early age. Her son (and Heather’s uncle), former lieutenant governor Bill Hobby, wrote of her in the Handbook of Texas:

She was only five or six when a temperance campaign swept Killeen, and at Sunday school all the small children were invited to sign the pledge and receive a Woman’s Christian Temperance Union white ribbon to wear. Oveta thought it over and refused. She had no particular desire to drink liquor, she granted, but she might wish to when she grew up and thought it best not to give her word unless she was sure she was prepared to keep it.

She inherited a firm belief in the importance of public service from her father, a state legislator, and evinced an early interest in the law. She attended both Baylor Female College (now the University of Mary Hardin-Baylor) and the South Texas College of Law, though she graduated from neither. At the tender age of twenty, she became the parliamentarian of the Texas House of Representatives, beginning a long career of public service, though her lone stab at electoral politics was a failure, as Uncle Bill notes:

At twenty-five she was persuaded to run for the state legislature from Houston, but was beaten by a candidate who whispered darkly that she was “a parliamentarian and a Unitarian.”

In 1931 she became the second wife of former Texas governor William P. Hobby, the president of the Houston Post and a good friend of her father’s; she was twenty-six and he was fifty-three. For the next decade, her life revolved around the newspaper business (she was successively the book editor, assistant editor, and executive vice president of the Post during the 1930s), community affairs (she was president of the League of Women Voters of Texas and served on the boards of various civic organizations), and her two children.

In 1942, she was appointed the first head of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), which later became the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). She became the first woman accorded the rank of colonel in the United States Army and worked tirelessly, in the face of deeply entrenched skepticism and prejudice, to establish the WAC as a legitimate branch of the service. (In 1945, in recognition of her efforts, she became the first woman to receive the Distinguished Service Medal.) Uncle Bill again:

The job she undertook was hard, often exasperating, frequently amusing, and sometimes heartbreaking. The new director had to travel constantly, speaking to large groups of men and women on the radical subject of enlisting volunteer women into the army. She traveled with an electric fan and iron, so that at each overnight stop she could wash, dry, and iron her khaki uniform—the only WAAC uniform in existence at the time.

After the war, she was active in the Democrats for Eisenhower movement, and in 1953 Ike appointed her the first secretary of the brand-new Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now the Department of Health and Human Services); she thus became only the second female Cabinet member in United States history. She resigned in 1955 to spend more time with her ailing husband (he died in 1964), and spent the next four decades overseeing the family communications business, which grew to include radio and television stations, and solidifying her standing as the first lady of Houston society. She died in 1995.

My own memories of her begin in the summer of 1981, when Heather and I, having just graduated from Williams College, embarked on an epic cross-country drive from Massachusetts to California and back to San Antonio.

En route to the West Coast, we passed through New Orleans, where we spent several days, and Houston, where we arranged to visit Mamaw. (Heather had made it clear that Mamaw was most definitely not the sort of grandmother one dropped in on unannounced for milk and cookies, so we called her secretary and made an appointment.)

On the night before our departure from the Crescent City, someone broke into our car and made off with all our worldly possessions (admittedly a modest pile), including Heather’s Williams College diploma and (this really hurt) our cooler full of beer. We were left, quite literally, with the clothes on our backs—in my case, a pair of cut-off jeans and a T-shirt bearing, in large letters across the chest, the slogan of the oyster bar in Boston’s Faneuil Hall (“EAT IT RAW”). We waited several hours, in vain, for the New Orleans police to show up before Heather announced that we had to leave; we simply could not afford to be late for our appointment with Mamaw.

We fairly flew over I-10 to Houston, pulling up at Mamaw’s house just in time. We were shown into a beautifully appointed sitting room and offered tea. The tea arrived, served in lovely bone china; I accepted a cup, and balanced it on my knee while we awaited Mamaw’s entrance.

Just before she entered the room, I looked down at the delicate cup and saucer resting on my bare, hairy knee, and suddenly realized that this meeting was not going to go well.

Sure enough, the temperature in the room seemed to drop several degrees when Mamaw entered and caught her first glimpse of me in my cut-offs and vulgar T-shirt, with my bushy beard and gold earring. What had I been thinking? Granted, we’d been in a hurry to reach Houston, but why hadn’t we stopped for even five minutes at a Dollar General Store and at least bought me a plain white T-shirt?

I escaped that awkward meeting alive, somehow, but for the next few years, whenever Mamaw called Heather and I happened to pick up the phone, I could feel the chill coming over the long-distance lines and through the receiver. “Hello?” I would say. (This was long before caller ID, of course.) “Is Heather there,” came the icy response—never “Hello, Martin,” or “How are you?”

Finally, after we married, Mamaw began, very gradually, to warm up to me. She became much friendlier on the phone, even asking me questions about myself and my work before asking to speak to Heather. We took our kids to visit her in Houston, having first threatened them with torture and dismemberment if they misbehaved; she seemed to enjoy them, though she never got used to the idea that she had a great-grandson named Tito. (“And how is little, er, Toto?” she would ask.)

She was also a little dubious about my ethnicity. The story goes that when one of Heather’s cousins announced that she was marrying a young man of Greek descent, Mamaw sniffed, “Well, we already have a Kohout in the family. I suppose we might as well have a Papadopoulos.”

I had of course always admired and respected her, and toward the end of her life I grew to love her as well. She was ferociously intelligent, determined, and opinionated, and yet she was also gracious and charming, and extremely funny—all qualities, by the way, she passed on to her daughter and granddaughters (and, so far as we can tell, to her great-granddaughters as well). I was fortunate indeed to know her, despite the somewhat, er, awkward beginning of our relationship.

Mamaw, I salute you. I hope that, wherever you are, you can see that I’ve cut my hair, trimmed the beard, and given up the earring. And that EAT IT RAW T-shirt disappeared years ago.

What we’re reading

Heather: W. S. Merwin, Migration: New and Selected Poems

Martin: Jerome Charyn, The Seventh Babe

I love this. Am putting it in my “save file” with other Madroño postings… after I share it.

This is the best. It made me laugh out loud as I remembered my phone conversations with Mrs. Hobby. She scared the bejesus out of me because she did not suffer fools kindly. I was never sure where she placed me. I always let out a big sigh of relief when our conversations ended.