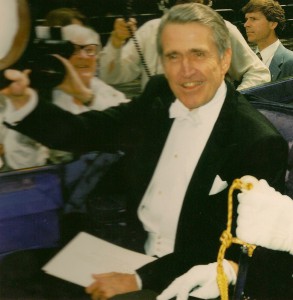

Heather’s father Henry E. Catto Jr. died on December 18, 2011. The following is an adaptation of remarks she delivered at his memorial service at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in San Antonio on January 7.

My friend Mimi Swartz wrote a wonderful piece in the November 2010 issue of Texas Monthly about the lovely and sometimes exasperating process of getting to know her father after her mother died. Pic Swartz had been one of my father’s dearest friends since before Mimi and I were born, but I read her piece with more than just the prurient pleasure of reading about someone you already know in excellent prose. She very accurately described a process I recognized in my relationship with my own father but that I hadn’t thought about yet. My mother, like Mimi’s, was the switchboard operator through whom most family information was routed. When she died, I was faced with what appeared to be a daunting task: getting to know my then-seventy-nine-year-old father without a mediator.

I don’t mean for a minute to suggest that he was somehow absent from my life. He drew silly cartoons on my lunch bags when I was in grade school, perhaps to make up for the fact that no one would trade lunches with me—my mother was an early adopter of what was then called “health food,” and the other kids utterly scorned my lunches. He scared the shorts off all his children (and his wife) when we made our yearly summer drive from San Antonio (where we lived at the time) to Aspen, Colorado, over a then-unpaved Independence Pass: he loved to pretend to lose control of the station wagon and hear us shriek with pleasure at our narrow escape. (My mother’s shrieking may not have been pleasure-based.)

Through my teenage and college years, he impressed on me the importance of being prompt (although I’m not, particularly). The sight of him sitting in a grumpy heap of plaid bathrobe at the bottom of the stairs late at night was one I learned actively to avoid. He also taught me the importance of looking up the meaning of words I didn’t know. One day he wrote me a note for school: “Please excuse Heather’s absence from school yesterday. She was malingering.” When I didn’t ask him what malingering was, he suggested that I look it up. After I did so and shrieked, “DAD-dy!” he wrote another: “Please excuse Heather’s absence from school yesterday. She was gold-bricking.” Not yet having learned my lesson, I had to shriek one more time before I received a satisfactory note; my love of dictionaries has continued to this day.

He drove me to Massachusetts from our home in northern Virginia for my freshman year of college at his own alma mater, pointing out places he had known and loved as we got nearer Williamstown. As we approached my dorm, he suddenly spluttered in outrage at the displacement of his beautiful old frat house by an architecturally unfortunate library. Aggravated as he was, he refocused his attentions to carry my station wagonload of stuff to the third-floor room and cried before he drove away, even as he continued muttering imprecations against willful artistic ugliness, an issue that vexed him all his life.

I also knew that he could be an unusually good sport. Political discussions, of course, were always central to our family’s common life, and my mother, who was a Democrat and always up for an argument, never let a political proclamation from my father drive by without pulling it over and checking its registration. She taught her children well, which means that it’s likely his whole family voted him out of a job he loved in 1992, when President Clinton came in. I never heard a word of recrimination. He didn’t stop trying to show me the true Republican light, however much he felt its glow in the past years had dimmed. In fact, in the end I was forced to admit that he might have some points worth considering.

I already knew these things about my father when my mother died: that he was funny, a stickler for precision in language, an advocate for order and beauty in the arts, and usually a very good sport. That’s not a bad list to start with, or even to finish up with. What I’ve learned about him in the last two years without my mother has surprised me and left me very grateful, despite the cost of the knowing.

Most of you who knew him have probably noted that I haven’t yet mentioned what might be my father’s most salient characteristic: his charm, which, having swum in all my life, I had ceased to notice. When I did notice it, I often thought of his charm as an accessory, a frill. Charm just wasn’t Serious. It wasn’t Deep. It was Frivolous.

In the past two years, Dad and I spent a considerable amount of time at M. D. Anderson, where I watched him “oozing charm from every pore.” What I came to realize after a while was that his charm was not directed just to the people who might be useful to him. It oozed all over the place in a cheerfully undisciplined flow. Cashiers in the cafeteria, janitors, doctors, volunteers, nurses, all laughed at his jokes, smiled at his suspenders and bow ties, graciously tolerated his corrections of their grammar, and responded to his courtly interest in them so that lightness and buoyancy tended to bob up where he was. I began to notice it in other places we went as well, this capacity to disarm people from all walks of life, people who might easily have dismissed him as a stuffy, inflexible elitist.

This is the backdrop against which I made my most unexpected discovery about my father: he had a capacity to ask genuinely for pardon when he had offended and to forgive when offended against. I have come to see his charm as an outward and visible sign of a deep humility, a bloom that became particularly noticeable to me after my mother died. It was something I had completely overlooked—and perhaps something he hadn’t known about himself and which may have sprung from the sharp compassion that can emerge from grief.

In the last two years we had many, many opportunities to ask for each other’s pardon. Although he had a pair of very expensive hearing aids, he rarely wore them, preferring to accuse me of mumbling and requiring me to repeat myself with frequency, followed by exhortations not to yell. One morning I was driving him somewhere and just lost my temper when told to stop mumbling and yelling yet again. “Maybe,” I said with some asperity, “you ought to consider apologizing to me for making me repeat myself over and over again when you could just put in your damn hearing aids.” He raised an eyebrow and said, “But it’s so much easier to blame you”—and then, just before I pulled over and throttled him, he truly apologized, although he did not put in his hearing aids.

We spent a lot of our time together arguing. We argued about his driving and his tendency to want to control his medical appointments without telling anyone about them. We argued about what he considered my tendency to worry and fuss. We argued about the need for nurses. We argued about the need for new kitchen appliances. We argued about moving the TV in his room to a place where he could actually see and hear it. Arguing with my father was not a novel experience. What began to follow the arguments was. Almost inevitably, I would get a call a few minutes after an argument, or a request for my presence, followed by a genuine apology, which in turn, allowed the same to be called forth from me. I learned that the moments of annoyance were never the last word. I learned to respect and be led by a depth of sweetness that I had previously judged to be frivolous. I learned how to love him all the way down because he showed me how to do it.

Learning to see the deep roots of his charm—which sprang from a genuine desire for peace at global and personal levels—I have come to see that my father was one of the blessed peacemakers Jesus called the children of God. That, in his own struggle with grief, he could reveal himself as this child of blessing was his greatest gift and example to me. Blessed are the peacemakers. Blessed is Henry Catto, with or without his hearing aids.

What we’re reading

Heather: Michael Chabon, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union

Martin: Erik Larson, In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin

Heather, that is lovely!

Tony xxx

As beautiful to read as it was to hear. (And I love the “dimmed” link.)

You describe the Henry that I knew and enjoyed for so many years. He was indeed completely genuine in every way. You are a worthy descendant, and I am so glad that I know you.

Heather, I am so thankful that Martin posted this on Facebook. It is beautiful, such an honest and loving tribute of a daughter for her beloved dad. You have quite a legacy of charm to uphold. Thinking of you and your family. xoxox

Diane

This lovely tribute makes me want to have had the honor to argue with your inarguably amazing father.

His charm and wit (and vocabulary) live on in you.

xo

Heather,

I’m so sorry about your father’s passing. Thank you for your lovely words, they remind me of my own father and men of a different generation.

Much, much love.

Oh, Heather. How I wish I’d had the honor of meeting your father, but I cannot help but also wish that a dinner party could’ve occurred with your parents and my maternal grandparents. Of course, the fun would be being a fly on the wall… (my gr-folks also are fans of not wearing their hearing aids; Grmo. is still a card-carrying member of Emily’s List, while Grpa was a “serious Republican” until Bush’s 2nd term). I’m so very sorry for your loss, and touched at the legacy he’s left you.

Words escape me. But not tears. Love!

Thank you for sharing this with all of us. Being with your father and mother in Woody Creek was always special. They will always be with us as great humane beings. Among your father’s many fine qualities was his common touch. We all felt comfortable, recognized, and respected in his presence.

Thanks, Heather, for giving us the gift of your father. Blessings to you and your family.

I second what Cynthia said. Truly extraordinary–you, your insight and capacity for love, and your father.

What an exquisite, moving tribute – we are all able to love and appreciate your father through your wonderful words, Heather. No malingering of any kind – except to read, and feel gratitude. Thank you.

Heather: I’m glad Martin shared your insightful, well-articulated and poignant tribute to your father. It’s clear each of you was a blessing to the other. Thank you!

Beautiful. I knew Henry from only a few visits to Woody Creek, and always believed his charm sprang not from simple politeness or hospitality, but from a genuine and sincere interest in all those around him. Thank you for confirming my belief and for sharing your life with Henry so eloquently.

Losing both parents left me feeling like a little life boat, bobbing about in search of its ocean liner. What a wonderful navigation you have made, tethering the three of you together here with clarity, humor, and grace. A lovely reading experience. Thank you.

Heather,

I love, love what you said about your father! So incredibly touching. It helped me clarify some of what I admire about my father — especially the connection between charm and humility.

Thank you,

Molly

What a wonderful tribute. I don’t think I ever met your father; I only knew him through you and his career. Having read your tribute, I can really picture him. Thanks, Heather.

Heather:

Hermosos pensamientos acerca de tu padre,,, (El Patron.), y me siento muy honrado y orgulloso de haber conocido a tan honorable persona y de haber convivido con el, la Sra. Catto y porsupuesto con todos ustedes sus hijos.

Dios te bendiga hoy y siempre.