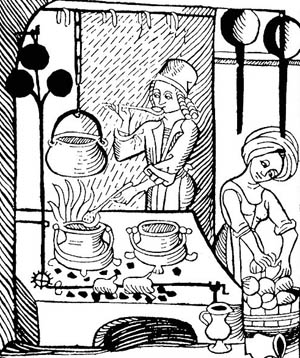

The season of hospitality is upon us, with all its pleasures and burdens. Known in the Christian tradition as Advent, it focuses on the need for preparation, both for the very intimate event of a baby’s birth and for the cosmic birth of a new order. One of my favorite images for the season, if I’m remembering rightly, comes from a series of woodcuts made by a northern Renaissance nun. In it, she imagines herself as a housewife, preparing for the coming company of the Child and the Judge by cleaning the house of her heart: dusting, sweeping, washing, polishing. The images refuse any pretensions to profound theology or high art; they are reassuringly earth-bound and homey. If you pay attention, you can almost smell the baking bread.

“Hospitality” is one of those words whose meaning has changed over the years. In our current culture, it often refers to an industry directed toward travelers or those in need who are expected to pay for its services. If hospitality isn’t a primarily economic exchange, it usually refers to the opening of home and hearth to friends, family, and associates.

In ancient times (or in places that still hew to ancient ways), hospitality wasn’t a service or an option; it was a necessity and a moral imperative. Before the development of institutional hospitality (hospitals, hospices, hostels), vulnerable individuals outside of the normal network of social relations—travelers, refugees, the sick, pilgrims, orphans, widows—were able to rely, at least for a while, on a code of hospitality that brought shame to those who were able and refused to engage it. Christine Pohl, professor of Christian social ethics at Asbury Theological Seminary, writes: “In a number of ancient civilizations, hospitality was viewed as a pillar on which all other morality rested: it encompassed ‘the good.’”

Curiously, the words “host” and “guest” are closely related etymologically, if they don’t actually come from the same source. Even more interestingly, “guest” shares an etymological bed with “enemy,” rooted in the notion of “stranger.” The idea that any of us might move from providing hospitality to needing it—to and from strangers—gives the word a kind of trinitarian energy that caroms from the poles of host to guest to stranger/enemy until the parts are indistinguishable from the whole. I don’t usually feel that charge when I check into a motel, but I think the hospitable artist nun knew that she was a part of that energy, as hostess opening her heart to the Child; as guest and sojourner on the earth; as stranger before the greatest mystery.

One of the reasons I’m thinking about hospitality, aside from the advent of Advent, is that today we’ll welcome seven guests, whom we have never met, to Madroño for the weekend. They’ll be attending “Deer School,” the brainchild of Jesse Griffiths, chef, butcher, and proprietor (with his wife Tamara Mayfield) of the Dai Due supper club and butcher shop. Deer School will include several guided hunts followed by instructions on how to field-dress and use the animal from nose to tail, followed by some really fine eating.

While I’ve been thinking recently about what it means to be a good host (new sheets and shower curtains), I’m also thinking about my role as guest, sojourner, stranger, enemy; after all, they are intimately connected. In last week’s Thanksgiving post, Martin wrote about the hospitable nature of the feast: “On Thanksgiving the acts of preparing, serving, and eating become consciously sacramental; the cook(s) giving, the guest(s) receiving, in a spirit of gratitude that can, sadly, be all too rare at other times of the year….” As one of the cooks this year, I was less attuned to what I was giving than to what had been given to me: the gorgeous vegetables from local farms, the fresh turkey from our over-subscribed friends Jim and Kay Richardson, and the freshly shot and skinned half-hog that unceremoniously appeared on the kitchen counter (and then spent eight hours roasting in a pit) after my brother, his son, our son, and Robert, the redoubtable ranch manager, went hunting early Thursday morning. The astonishing abundance and hospitality of the land was quite literally overwhelming: half a 150-plus-pound sow is a lot of meat.

I’m blundering onto mushy and possibly treacherous literary territory here, I know: Mother Earth nourishing her offspring, big hugs all around. But I’m increasingly grateful for the bounty of the place and hope the same for those who come here seeking community, solitude, rest, refreshment, and, yes, fresh deer meat. We call Madroño Ranch ours by some weird cosmic accident; the more we know it, the more we know that it belongs to itself or to something even broader, wider, more generous. What we hope now is to avoid being the nightmare guest/enemy, the one who comes and overstays his or her welcome within twenty minutes, who demands foods you don’t have, strews clothes all over the house, leaves trash and dirty dishes in the guest room, noisily stays up late, assumes you’ll do all the laundry, and never says please or thank you. Who seems to think he or she owns the place.

We all know places where that’s exactly what has happened; for me, one such place is the stretch of Interstate 35 between San Antonio and Austin, which Martin and I drove last Sunday morning, and which is almost completely lined with outlet malls, chain stores, fast-food franchises, and other such marks of our collective thoughtlessness. Somehow, we’ve managed to promote the idea, especially in the American West and particularly in Texas, that among the rights accruing to property owners is the right to destroy or devalue their property in the name of short-term economic gain. In fact, destroying property may be seen as the ultimate proof of ownership.

I struggled in an earlier post with the idea of land ownership, and I struggle with it still. All land came as a gift at some point. Not literally to its current owner, perhaps, but the land still bears the trace of its giftedness somewhere on that deed. In this season when we prepare for the arrival of guests, giving the gift of hospitality, or head somewhere hoping to be good guests, bringing gifts of thanks, it can be easy to forget that we are also always empty-handed strangers, constantly looking for a wider hospitality than we are ever able to offer or sometimes even to know that we need. We’re only a week past Thanksgiving; this is as good a time as any to thank the land that sustains us. Without it, we can never fill a house with the smells of baking bread and roasting meat—or any of the other things that sustain us.

What we’re reading

Heather: Wallace Stegner, Crossing to Safety (still)

Martin: Ben Macintyre, Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory