Some say you’re lucky

If nothing shatters it.But then you wouldn’t

Understand poems or songs,

You’d never know

Beauty comes from loss.It’s deep inside every person:

A tear tinier

Than a pearl or thorn.It’s one of the places

The beloved is born.

April was National Poetry Month, which might or might not be a silly thing, but it has prodded me into thinking about poetry and my erratic relationship with it. When I received my two degrees in English, I was emphatically a fiction person. Poetry made me anxious because I could never figure out how to read it or what it was supposed to mean. My poetry textbooks from college and grad school are studded with frantic and useless annotations: cross-references to other poems by the same author, details about textual corruptions or variations, or underlinings directed by the professor that have no meaning for me now. Only rarely did I mark something just because I liked it, and then I worried about having made such a bold declaration. What if it didn’t mean what I thought it meant? What if someone discovered that I just didn’t get it?

I still have no idea what many poems mean, but I more often read poetry than fiction now. I use poetry when I teach and pray. I even read it just for fun. I sometimes write the kind of poetry that gave me brain freeze twenty-five years ago. How did this sea change come about? It began, I think, when I went to seminary and was forced to confront the Bible, a book I had never read and suspected that I wouldn’t like and feared would make me stupid. (I still wonder who was on the admissions committee that admitted me: Groucho Marx?) At first the familiar structure of the classroom allowed me to keep it at arm’s length. Memorize, analyze, parse, criticize. What do you do with a God who smites and punishes and condemns? Who needs his ego massaged with praise all the time? And yet I couldn’t help noticing that many of the psalms, the Song of Solomon, and the Jesus who considered the lilies all addressed a force they considered entirely trustworthy, entirely beautiful, the genesis and end of all desire. I could not see what they saw when I read with a lens of suspicion. And, despite my distrust, I wanted to see what they saw.

I began reading aloud, in groups, slowly and repetitively. It was sometimes helpful to have literary and historical information to draw on, but I was more often hobbled when I came to passages like this from the Letter to the Hebrews: “Indeed, the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing until it divides soul from spirit, joints from marrow; it is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart. And before him no creature is hidden, but all are naked and laid bare to the eyes of the one to whom we must render an account.”

It was beautiful. I knew that it was somehow true. I had no idea what it meant. Yet over and over, I found myself run through by the language of scripture, knowing I had been wounded but unable to bind or even find the wound. In the company of similarly riven souls, however, I started finding another way, not so much to read as to be read. Instead of seeking experience—that giddy adrenaline ride of a narrative—I found a place from which to see my own experience, my self in relation to a much greater whole. I was like a one-eyed creature that had been given another eye; reality began to acquire a previously unsuspected dimension.

The April issue of The Sun contains an interview with Philip Shepherd, a British writer and actor, whose career has led him explore the implications of the little known fact that human beings have two brains, one in the head and one in the gut. This is not a fanciful or metaphorical claim. Nuerogastroenterology, a new medical field, studies the web of neurons lining the gastrointestinal tract that send signals to the body independent of the cranial brain. Shepherd is not a medical professional but uses the research in the field to examine the cultural and philosophical implications of this “pelvic brain.” Says Shepherd:

Our culture doesn’t recognize that hub in the belly, and most of us don’t trust it enough to come to rest there. Our story insists that our thinking occurs exclusively in the head. And so we are stuck in the cranium, unable to open the door to the body and join its thinking. The best we can do is put our ear to the imaginary wall separating us from it and “listen to the body,” a phrase that means well but actually keeps us in the head, gathering information from the outside. The body is you. We are missing the experience of our own being.

The intelligence of the pelvic brain is not rational, conscious, analytical or abstract; rather, it arises in the way an enormous flock of starlings alters its course like a single organism. Well, you might say, I’m not a flock of starlings. But we all have an astonishing sensitivity—a sensational sensitivity—to our perpetually changing environments, astonishing in its almost invisible routineness and its capacity to integrate multiple levels of information. It’s an intelligence we often take for granted or don’t acknowledge as intelligence at all, but it allows you to negotiate your way through space, to remember passages of music, to understand arithmetical relationships, to love or know joy. Our task is not to privilege one brain over the other but to learn to coordinate them, according to Shepherd. He uses a lovely analogy to illustrate what this coordination looks like: the astronauts who took the first photos of the earth from outer space brought them back to earth, giving us a new perspective on our planet’s fragility. We responded with environmental initiatives. We were sensitized.

Culturally speaking, though, Shepherd says that those of us who inhabit the “first world” are like astronauts who are stuck in orbit around the head, unable to descend back home to the belly, where the gathered information can be integrated and sensitize us to the great complex flow of the world we inhabit:

Our culture has a tacit assumption that if we can just gather enough information on ourselves and the world, it will add up to a whole. But when you stand back and look at something, there is always something hidden from you. The integration of multiple perspectives into a whole can happen only when, like the astronaut bringing the photo back to earth, we bring this information back to the pelvic bowl, back to the ground of our being, back to the integrating genius of the female consciousness. The pelvic bowl is the original beggar’s bowl: it receives the gifts of the world—the male perspective—and integrates them. As you bring ideas down to the belly and let them settle there, they sensitize you to who you are and give birth to insight. Our task is to learn to trust that process.

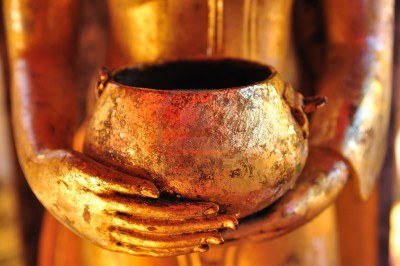

The belly brain as begging bowl, receiving the gifts of the world. In some Buddhist traditions, monks are mendicants who own nothing but their robes and their begging bowls, in which they receive offerings of food or other gifts from the lay community. These gifts are not considered alms but rather are part of an exchange in which the community supports the monks physically and the monks support the community spiritually. So quite literally, every human being carries a begging bowl to the world, an intelligence that establishes itself in emptiness, in poverty, in suffering, in sensitivity, in loss. Without that bowl, we have no place for the works arising from the cranial brain to incubate and mature before they enter the world. Without cross-pollination from the pelvic brain, the fruits of the cranial brain are stunted and distorted, rooted in the illusion that we are separate from the natural world and thereby at odds with it. Aligning the two intelligences gives us the opportunity to see holistically, with the depth of binary vision.

Given my initial take on the Bible, it seems poetically just that it should lead me to a less literal, more personally demanding way of reading, one that required some self knowledge before I could make any sense of it. Like scripture, good poetry is a gift in the begging bowl, pressing the reader to claim hunger and absence before the equally great gifts of abundance and presence come to view. In his wrenchingly beautiful volume of poetry, Concerning the Book That Is the Body of the Beloved (from which the poems at the beginning and end of this post are taken), Gregory Orr looks at the world with at least two eyes, that trinitarian third eye of the heart figuring somewhere in this body of stern and tender wisdom. I don’t mind that I don’t understand it all; reading it, I find that I have been seen, known, understood.

I guess I’m fine with National Poetry Month.

The beloved has gone away.

Always, this is the case.

Each moment turns on its hinge

And loss is there, loss

Announcing itself as absence.But that’s because we’re looking

Backward, looking in the wrong

Direction: so desperately clinging

To a last glimpse of the beloved,

As if loss itself is what we loved.And all the time the beloved

Is coming toward us, is arriving

Out of the future, eager to greet us.

What we’re reading

Heather: Gregory Orr, Poetry as Survival

Martin: Rachel Hewitt, Map of a Nation: A Biography of the Ordnance Survey

Wow. Just, wow. Thank you, my dear friend. This is as beautiful a thing as I have read in a very long time.

Dearest Heather,

Gee, I feel smart after reading your lovely, thought-provoking words about our two brains. I think I followed you all the way through, and it makes me feel like a grown-up. I have always been in awe of the evident intelligence that you and Martin toss around like a volleyball. As you know I often dwell in La-La-Land, where reality is only a seven-letter word. I try to find the happy trails of Roy Rogersville, which makes for a false, rose-colored garden that I surround myself with. We all get feelings about situations and often jump to conclusions based on those feelings. I am particularly bad about judging people by my “gut feelings” about them. Maybe I should listen to my head a little more. Often your mother and I had the same reactions to people and places. Your dad, in turn, thought we were a little wacky. However, we were usually right but not 100 percent. I’m way off the track now when I get to analyzing the past. Love to you, Susan

Sweet Heather, thank you for bringing tears of joy to me by reading your beautiful words. In awe, Kathryn

Heather – Thank you, thank you, thank you. This is marvelous writing that makes me feel grateful to be alive and in wonder of the world.

heather, dearest, how sweet it is to read you–and in such masterful, moving form. god knew what s/he was doing on that admissions committee. thank god for you.

When I read this remarkable piece, I tried to come up with a word and the only one that arose was “grace,” a condition I have experienced but which always contains a lot of mystery. I also realized that I could never write a piece like yours, as I have not experienced the pain and loss you have endured and over which you have somehow prevailed. Thanks. Hall

You and your words, nothing better. I read the Shepherd article in The Sun when it arrived and used his belly brain philosophy in my last retreat as an approach or process to being present. It was remarkable. Thanks for sharing your thoughts. I’ll look forward to sharing another hug in the near future.