Something that might seem fragile—a group of words arranged on a page—turns out to be indestructible. (Ed Hirsch)

Sometimes—maybe even often—I wonder why in heaven’s name it ever seemed like a good idea to open a residency for environmental writers and artists. It can seem like an awfully precious response to the unholy forces in the world, to the seemingly implacable powers that sneer and smear and humiliate, ravage and amputate, and leave sterility in their wake. Surely there are better weapons, ones more powerful and direct, to fight the battle. Let’s face it: writers and artists don’t get a lot of press as warriors.

To top it off, this is Holy Week, when those demonic powers seem to have won. Today is Good Friday, and the Word is tortured, broken, murdered. Silenced. It’s a day that can be particularly horrid for writers, killing any impulse to communicate.

And yet, and yet… we spent last weekend at the tenth annual Poetry at Round Top festival at the Round Top Festival Institute, in the rich rolling countryside between Austin and Houston. Just the drive to Round Top presaged a mythic encounter, the possibility of resurrection: despite the extreme drought conditions in central Texas, patches of courageous bluebonnets and Indian paintbrushes bloomed. Later than usual, apparently aware of the scorching to come, live oaks and pecans unfurled their precious leaves, whose sweet green humidity was instantly thrashed by stiff dry southern winds. Wildfires are blazing across the state: the morning we left, we smelled smoke from the Rock House fire in Marfa, 450 miles away. And yet spring unfurls its banners.

“So what? And, by the way, mythic encounters are so-o-o-o 1970s,” says the legion of demons in my head.

“Shut up,” I explain, thinking they might be right. It’s not as if spring has any choice. What’s courageous about doing what you can’t help doing?

My little herd of demons kept up its background sneering once we got to Festival Hill, a strikingly beautiful and eccentric campus of older wooden buildings enlivened by lavishly unlikely additions: stone grottos and follies, great tumbling fountains, stone cherubs and goblins and saints, whimsy and careful craftsmanship everywhere.

“Nice,” they said. “You’re doing a lot to challenge Big Ag and stop carbon emissions by ooh-ing and aah-ing and hanging out with a bunch of poets.”

“Shut up AND go away,” I said, enunciating carefully.

They thought that was funny.

We all settled down when Ed Hirsch shambled up to the podium. Hirsch is a much-published poet and teacher and author of How To Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry, a “surprise best-seller” only to those who haven’t read it. He’s one of those gifted speakers—warm, passionate, wise—who makes you wish that he could keep talking until he has nothing left to say.

He spoke about the power of lyric poetry to “allow the intimacy of strangers,” sometimes separated by centuries, even millennia. Lyric poetry, created in solitude, calls wildly unlikely community into being. He recounted his first contact with the power of lyric poetry, when he was electrified reading one of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “terrible sonnets.” He—a Jewish student at Grinnell College in the 1960s—was stunned to find someone—a British Victorian Jesuit priest, long dead—who could describe his feelings of isolation and distress better than he could himself.

Even deeper than the jolt of recognition, the young Hirsch became aware that Hopkins had made something from his desolation: “Holy shit!” he remembered thinking. “This thing is a sonnet!” He felt Hopkins’s “tremendous generosity to take that isolation” and create something of beauty from its wretched depths “so that I might come along later to be comforted.” Poetry in its very structure is hopeful even when it despairs, Hirsch believes, because poets must imagine “a reader on the horizon,” someone to whom the poem must be directed, in order to write at all.

Poetry as an act of generosity to strangers, as the creation of intimacy across divides of time and culture: these hospitable acts require courage, especially in a fearful time.

“How convenient for your chicken-hearted, lazy soul,” said my loitering demons.

“Don’t you slander chickens, you morons,” I replied irritably, having forgotten for a minute that they were there.

“Oh, we’re cloven by the thrust and parry of your rapier wit,” they smirked. “Oh, we’re slain!” And they fell all over each other, howling.

“Oh, shut up,” I said.

The next morning—Sunday, no less—we sat in the beautiful deconsecrated chapel used for more intimate readings, sunlight pouring through the neo-Gothic windows into the meditatively dim sanctuary. We listened to Chris Leche, a poet who has taught in war zones for the past ten years. She read three of her own poems along with a stunning essay by one of her students who was fighting in Afghanistan. He wrote about his struggle not to stand too long in the soul-destroying acid of hatred, most vividly triggered when he saw a ten-year-old Afghani boy, face filled with rage, stare at him and then pointedly pull a finger across his throat. Even as fury for revenge rose in him, the soldier remembered that this was a child, a child whose soul was already poisoned and dying. His words were like smelling salts to those of us seated in the sanctuary, jolting us into consciousness. This soldier had reached across time and distance and shaken us awake.

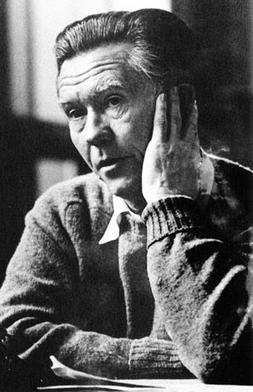

After Leche and several others (including our new friend Barbara Ras) read, we watched a documentary entitled Every War Has Two Losers about the great American poet William Stafford, who was born in 1914, the year in which World War I erupted, and died in 1993. (That’s him in the photo above.) From his youth, he was convicted by the certainty that violence cannot end violence, but only perpetuate it. He was a conscientious objector during World War II and spent the war in camps for conscientious objectors in California and Arkansas. He spent the rest of his life bearing witness to the possibility of peace as positive force, rather than a mere cessation of war. In the introduction to the book of the same title, Stafford’s son Kim, also a poet, writes:

as a child my father somehow arrived at the idea that one does not need to fight; nor does one need to run away. Both these actions are failures of the imagination. Instead of fighting or running you can stand by the oppressed, the frightened, or even “the enemy.” You can witness for connection, even when many around you react with fury, or with fear.

Many contemporary poets influenced by Stafford’s willingness to stand in the uneasy role of witness were interviewed in the film, including Robert Bly, Coleman Barker, Naomi Shihab Nye, Maxine Hong Kingston, W. S. Merwin, and Alice Walker. They all pointed to his insistence that we do the hard work of imagining “the enemy”: that we wonder about his family, his childhood, his children; that we imagine what might have led him to consider us as enemy; that we refuse ever to lose sight of his humanity, of his hunger, joy, and pain. The discipline of always imagining the enemy as clearly as he could imagine himself left Stafford, like the spring, unable to do anything but bloom with love of neighbor.

Stafford wrote: “Save the world by torturing one innocent child? Which innocent child?” He wrote: “Is there a quiet way, a helpful way, to question what has been won in a war that the victors are still cheering? … Or does the winning itself close our questions about it? Might failing to question it make it easier to try war again?” He wrote: “Keep a journal, and don’t assume that your work has to accomplish anything worthy; artists and peace-workers are in it for the long haul, and not to be judged by immediate results….”

He wrote and decades later I, like Hirsch first reading Hopkins, was electrified. I felt seen, known. When my demons woke up and started jeering, I asked them politely to come in. I wanted to know (maybe) where they were from. Ha! they said. You wish, they said. Yes, I said. When I’m brave enough, I think I do.

So many courageous poets at this festival, living and dead, bore witness to the glory and depravity of the human condition. Such a community of witnesses. Maybe spring really will come again (even if just barely this year). Maybe Jesus really will rise from the dead. Maybe it’s not ridiculous to open a residency for environmental writers and artists, to provide a haven for those whose efforts might electrify others to work for beauty, for harmony, for wholeness. For salvation.

What we’re reading

Heather: Barbara Ras, The Last Skin

Martin: Emma Donoghue, Room

Oh my yes. I think we time-share some of the same demons, Heather. And, I’m with you. Given the choice, I’ll choose to be on the side of beauty, harmony, and salvation every time. We part ways on wholeness, since I don’t believe in it, but 3 out of 4 ain’t bad. xoxo J

You say that as if chicken hearted was a bad thing?

Felices Pascuas!

Thank you for another great blog entry.

Heather, I am suddenly tearful … perhaps it is because I happened to read your blog while listening to my “Alan Silvestri Radio” station on Pandora, perhaps it is because I had a precious nephew fight in Iraq and we counted the days until he was safely home, perhaps it is because I am days away from watching my last child leave the nest, perhaps it is because you topped it off with one of my favorite songs by Marvin Gaye combined with amazing photographs illustrating frustration and sadness (and a little hope) through the years, but I am guessing it’s mostly because you’re such a good writer … a poet in my eyes.

Heather – Yet another moving entry that stopped me dead in my tracks on a busy Saturday afternoon. Thank you.