One of the many notable gatherings Martin and I participated in this past weekend was the opening of my sister Isa Catto Shaw’s show at the Harvey/Meadows Gallery in Aspen, Colorado. In a series of watercolors and collages, she took the dark, mute burden of grief over the death of our mother and worked it into beautifully articulate packages, in some ways (perhaps) making that grief more easily borne because it is shared with a community of unknown mourners who see the paintings, with the community of artists from whom she has drawn inspiration, and from the community in which she and her family live. As far as I could tell, the opening was a wonderful success, the gallery full to overflowing as Isa and the ceramicist Doug Casebeer, with whom she shared the show, each spoke movingly about the impetus behind their individual efforts.

Knowing that she had been working like a madman for several months, I was glad (and deeply moved) to see the results of her labors. And aggravated. We’ve been talking since our mother died about a collaboration of my poetry and Isa’s art to be entitled “Blessings of a Mother.” Isa’s done her part, and it’s intimidatingly beautiful.

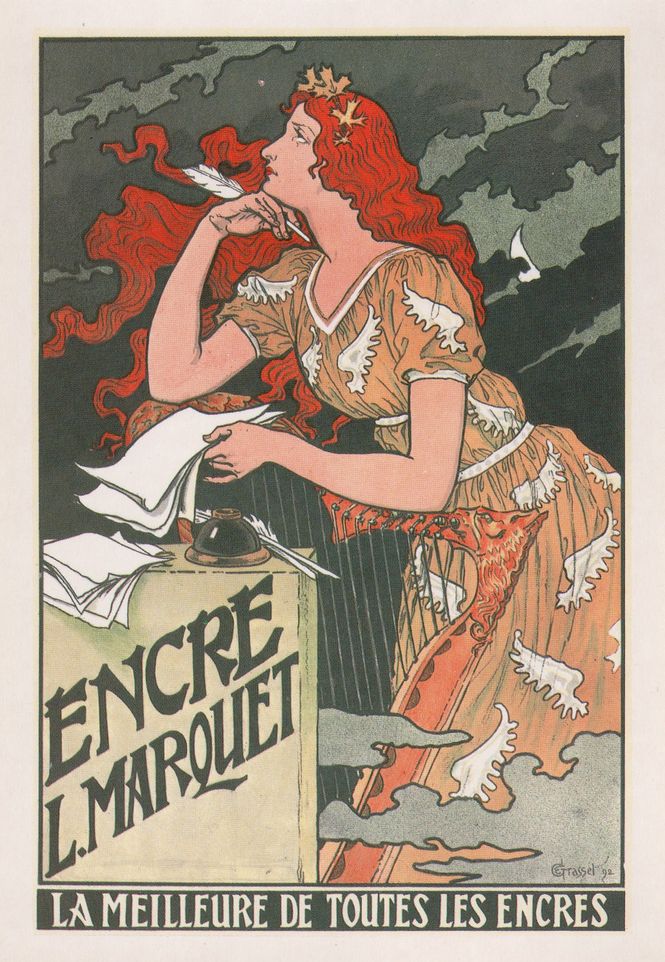

I, on the other hand, have done squat. This doesn’t mean I haven’t thought obsessively about the project or that I haven’t written multiple lists of topics and scraps of lines and stillborn poems. It does mean that I’ve been willing to be endlessly distracted and grumpy about it. I’ve developed all sorts of hypotheses about why I’m not writing and what I might do about it, most of them ultimately involving running away from home. My favorite defense against the terrorism of the blank page is to read, figuring that in doing so I’m in the company of someone else who has faced, at least temporarily, the tyranny of That Which Demands Expression And Remains Unexpressed. Plus, if I’m reading, I can’t write.

So here’s what I’m currently reading to fend off—and perhaps eventually to outsmart—the intimidation tactics of the blank page: Standing by Words, a collection of essays by Wendell Berry, in particular the title essay and its assertion that the primary obligation of language is to connect the idiom of the internal self with the multivalent tongues the self encounters in community, both human and otherwise. When language loses that capacity—a loss currently encouraged by the forces of industrial technology—both the self and its community languish in their isolation, succumbing eventually to a fatal disconnection from the web of love and life.

As always, Berry is defiantly unfashionable, insisting on the possibility of “fidelity between words and speakers or words and things or words and acts.” He believes that genuine communication is possible, even if its processes are ultimately mysterious and unavailable for dissection by specialists. The life of language is rooted in community and by the precision that life in community necessitates: “It sounds like this: ‘How about letting me borrow your tall jack?’ Or: ‘The old hollow beech blew down last night.’ Or, beginning a story, ‘Do you remember that time…?’ I would call this community speech. Its words have the power of pointing to things visible either to eyesight or to memory.” Community speech doesn’t imagine abstract futures; rather, it deals with what IS. It creates a walkway between internal, personal systems and external, public systems. Community speech registers the need to include both objective and subjective experience; it deflects the argot of specialists; it recognizes spheres of being beyond its domain. Says Berry:

If one wishes to promote the life of language, one must promote the life of the community—a discipline many times more trying, difficult, and long than that of linguistics, but having at least the virtue of hopefulness. It escapes the despair always implicit in specializations: the cultivation of discrete parts without respect or responsibility for the whole…. [Community speech] is limited by responsibility on the on the one hand and by humility on the other, or in Milton’s terms, by magnanimity and devotion.

Although I would argue with Berry’s assertion that all specialists are without awareness of their place in the “whole household in which life is lived” and thereby exclude themselves from the liveliness of community speech, I hearken to the limits he sets on speech, limits that protect the tender shoots of hopefulness, a crop that can be distressingly rare in an often grief-stricken world.

Forgive me. For an essay that aims, in part, to wrestle with ways to express the specificity and universality of grief, my language is so far distressingly abstract, a symptom, I suspect, of my current stuckness. I just received a note from an acquaintance who recently lost her husband to pancreatic cancer; she wrote that although she and her daughter have prepared for his death for a year, “it is like the bad dream where you show up for an exam without having read the book, in your PJs, totally unprepared.” I was struck by the generosity of the image, by her assumption that, though I have not experienced her particular and devastating sorrow, I could somehow imaginatively engage with it, and that we both belonged to the same community, despite the fact that we’ve only met twice before.

Writing is usually perceived to be a solitary pursuit, and in a very literal way it is. I’m trying to remember, however, that when I stare at the blank page or screen I’m seldom alone. (I’m not referring to the cats who often take naps behind me on my chair.) Trying to remember: trying to listen for the cloud of witnesses, the dead and the unborn, that root us in the past and impel us toward the future. I found Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies compelling after my mother’s death, in part because their language is so rich and their meaning so elusive, like a whispered conversation from another plane of being. In the translation by J. B. Leishman and Stephen Spender, they begin with this lament:

orders? And if one of them suddenly

pressed me against his heart, I should fade in the strength of his

stronger existence. For Beauty’s nothing

but beginning of Terror we’re still just able to bear,

and why we adore it so is because it serenely disdains

to destroy us. Every angel is terrible.

And so I repress myself, and swallow the call-note

Of depth-dark sobbing.

Although Rilke refuses to call on the angels, they soar in and out of the poems, weaving them together, helping create a complex whole from parts threatening to hurtle toward meaninglessness and isolation.

I’m usually suspicious of angel-talk, but Wendell Berry and my widowed acquaintance and my sister all remind me that I am—we are all— surrounded by angels, by community, even when we don’t sense its presence. When we are deaf to its song, we are deaf to our own.

Now if they’d only settle down and write those poems for me. Or at least recommend some nice writer’s residency where I could get them started.

What we’re reading

Heather: Wendell Berry, Standing by Words: Essays

Martin: Rebecca Solnit, Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas