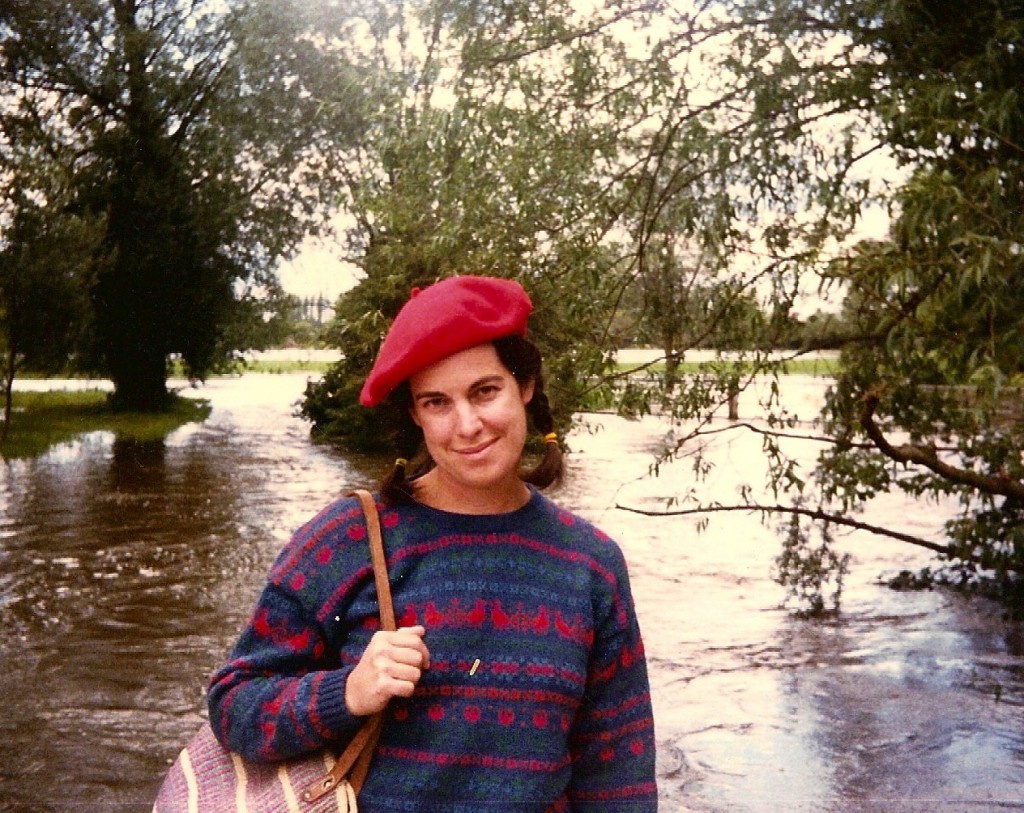

As many of you know, Heather Catto Kohout, whose idea Madroño Ranch: A Center for Writing, Art, and the Environment was, died on October 17, 2014, nearly three years after her initial diagnosis with metastatic cancer. Her obituary gives only a faint idea of the breadth and depth of her intellect and engagement, so it seems appropriate to devote this edition of “Free Range” to her memory, specifically to the words her beloved children Elizabeth, Tito, and Thea offered up at her memorial service at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Austin on October 23.

Thea (excerpt from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”):

What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?

They are alive and well somewhere,

The smallest sprout shows there is really no death,

And if there ever was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it.

And ceas’d the moment life appeared.

All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

Has anyone supposed it lucky to be born?

I hasten to inform him or her it is just as lucky to die, and I know it.

I pass death with the dying and birth with the new-wash’d babe, and am not contain’d between my hat and boots,

And peruse manifold objects, no two alike and every one good,

The earth good and the stars good, and their adjuncts all good.

I am not an earth nor an adjunct of an earth,

I am the mate and companion of people, all just as immortal and fathomless as myself.

(They do not know how immortal, but I know.)

Tito:

Good morning. On behalf of our family, thank you for coming.

Some of my first memories of my mother are of strength and power. More specifically, of being picked up and carried on a long hike in Colorado because I couldn’t keep up with her leisurely thirty-mile-an-hour pace. She could spend an afternoon nipping cedar under a remorseless August sun as easily as she could drive a Suburban full of screaming middle-schoolers from Austin to Mexico for a church trip. But as I got older, I saw her strength manifest itself in less obvious ways. She gave of herself freely and completely to good and just causes, from immigration to environment, and insisted that her children do the same. And I now understand better the strength and compassion she showed throughout both of her parents’ passing. She was the world’s strongest woman.

She wasn’t just strong, though. Her boundless intellect was just as amazing. It took me a long time to understand that not everybody’s mom analyzed Eckhardt Tolle and Anne Lamott. That not everybody’s mom read to them, and discussed the moral and metaphysical implications of talking cats or feudal society with them. That not everybody’s mom would cock her head, furrow her brow, and skewer anyone she met with a genuine and limitless curiosity. But she wasn’t grudging with her knowledge. Rather, she produced more information than she took in, and not just in her beautiful poetry and lyrical prose. Her entire life was a dialogue with the world, whether the world knew it or not. She never met a person she couldn’t teach and couldn’t learn from. Priests, artists, hotel maids, professors, state meat inspectors: she never met anyone who didn’t feel, after an hour’s worth of conversation, that they hadn’t known her and loved her for decades. I recall my panic as a child when she would fix her attention on one of my friends, or my teacher, or the plumber who came to fix the dripping bathroom sink, and ask them to tell her about themselves. And they would tell her, trusting that she would hear them and carry their struggles herself, just because she could.

Despite the strength of her body and her mind, though, she never tried to overpower anyone, to bludgeon them into doing her will. Instead, she treated every person she encountered with respect and dignity, regardless of the circumstances in which they met. She was equally capable of chatting with illegal immigrants as with former presidents of the United States. As a kid, the mixture of embarrassment and pride I felt at seeing her ask the gas station attendant how his wife’s surgery had gone was too much for me to understand. Now that I’m older, the pride remains, but it’s mixed with astonishment that she could remember everyone she met, remember their stories and their worries and their hopes, and offer support and comfort and advice as needed. That she was always available to family, friends, acquaintances, and strangers. That she was never rude or dismissive or unkind to anyone.

Trying to understand her is a process, and the process hasn’t ended. It won’t ever end. The longer I remember her, the more things come bubbling up from where the past hid them to surprise me with delayed insight into her strength, her intellect, and her grace. She’s no longer here, but this is not the end. She will remain with us, reflecting and refracting and magnifying herself into our lives to inspire, awe, and delight us, as she always has. And although it may not seem like much, it will, like her, be sufficient and abundant for us.

Elizabeth:

I’ve never noticed fireflies here in October, but I’ve been seeing them at dusk since around the time my mother began hospice. When I initially noticed them, on a run around my neighborhood, the first thought that popped into my head was that the fireflies were bits and sparks of my mother’s soul as it began the difficult work of disentangling itself from her body. I know that’s not scientific, not reasonable, and doesn’t make sense. I know there’s a more logical explanation for these fireflies out there, that maybe they’ve always been here this time of year, but I know my mother was someone who was at home with contradictions and poetry and big ideas, so I can’t quite let go of the notion that these brief and brilliant flashes of light are somehow a part my brilliant mother.

I love that Mom chose Whitman for this service. I can’t think of a poet better suited for a celebration of life, and Thea chose a perfect passage. There’s another part of Leaves of Grass that’s been rattling around in my head, though, and that’s the bit where Whitman asks, “Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” In putting together these thoughts about my mother, I’ve found myself tugged in contradictory directions: Do I talk about her love of being in motion and of the outdoors, or her love for stillness and meditation? Her strengths as a conversationalist or as a listener? Should I mention how she danced to Prince and Michael Jackson in the kitchen, or how she sang to Joni Mitchell and Emmylou Harris in the car? Her endless patience with children and friends, or her quick exasperation with lazy thinking, discrimination, or, perhaps worst of all, filling out forms? Her sense of humor or her serious intellect? Her deep commitment to the environment or her deep love for the Suburban she drove in the ’90s? The more I try to contain her within a narrative arc, the more deftly she slips away. Really, it’s not so different from chasing a firefly and losing it in the dark once the light stops flashing.

In some ways, I wonder if this isn’t Mom pranking me—daring me to figure her out, then darting away at the last second. She had a strong mischievous streak. In high school, she and I drove back from Colorado to Texas together. We spent a night in Taos and, on a whim, adopted a tiny, bright white, fearless kitten we saw through the window of a carpenter’s workshop when we were walking back from dinner. The kitten wasn’t even up for adoption, but Mom decided she belonged with us and sweet-talked the carpenter, and the next thing I knew we were speeding through the desert with Minnie the kitten cavorting across the dashboard. We did not tell my father about it until we returned home, where she pretended to be deeply sorry for bringing yet another cat into the family, but we all knew she didn’t mean it when she burst out laughing at the kitten’s antics in the middle of her apology.

And that laugh—my mom had one of the world’s great laughs. I think anyone who’s ever eaten dinner with my family knows that laugh and the lengths we went to in order to hear it. I don’t remember exactly when or how this tradition began, but for the past several years we’ve read a David Sedaris essay about Easter in France out loud over Easter dinner. It’s a fantastic essay on its own, but we don’t read it strictly for literary merit. Rather, we read it because every year without fail it made my mother first shake, then howl, and eventually weep with laughter, until the rest of us were helpless with laughter too. These are some of my most treasured memories.

In the last few months, as my mother’s health deteriorated, I found myself becoming more and more grateful for her laughter, for that bright flash of light that seemed to shine all the more brightly as everything around it got darker. In the last long conversation I had with her, I asked for her thoughts about marriage and raising a family and, while language was already starting to slip away from her, she still got her main points across. Mostly what she talked about was how much fun she’d had. Life with a husband and children had been exasperating, exhausting, confusing, and much harder work than she’d expected, she said, but it had also been infinitely more fun. That’s what she kept repeating: I had the best time, we had the best time, it was the best time.

And so it was. Of all the best times we had, the one I can’t get out of my head is of an early summer evening. I was about ten. We were walking the dog together and the night was warm, but the heat from the day was gone. We got to the open field around the corner from our house and the three of us kids took off through the grass and trees, shrieking, the dog and my dad running alongside us. As the sun set, I noticed that the fireflies had arrived for the summer. When I turned around to check for my mom, she was about twenty-five yards behind us, illuminated by a street lamp, with flashes from the fireflies all around her. “This is happiness,” I thought.

What I’m reading:

Jane Austen, Persuasion