“… most ranchers and farmers in the West care as much for the health of their land, air, and water as any member of the Sierra Club.” (Mark Dowie)

This was the second September in a row in which we decamped for two weeks to Point Reyes Station, California. The town, with a population of about 350, is in western Marin County, an hour north of San Francisco; it lies at the foot of Tomales Bay, which separates the Point Reyes peninsula from the mainland, and is a gateway to the Point Reyes National Seashore, some 70,000 acres of pristine beaches, rocky cliffs, historic dairy farms, redwood and eucalyptus trees, and tule elk. It is one of the most beautiful parts of a beautiful state, popular with hikers, kayakers, campers, horseback riders, and mountain bikers.

Point Reyes Station is also a foodie mecca, even by the rarefied standards of northern California. The nationally renowned Cowgirl Creamery is based here; the Saturday morning farmers’ market at Toby’s Feed Barn bears witness to the stunning variety and fertility of the surrounding farms and ranches; and the town features several fine restaurants, including Osteria Stellina, and a variety of enticing nearby dining options, including Saltwater, in nearby Inverness, and the renowned Hog Island Oysters, a few miles up Highway 1 on the eastern shore of the bay.

Natural beauty and agricultural plenty, plus a temperate climate: Point Reyes has it all. Even though Tomales Bay actually rests atop the dreaded San Andreas Fault, which means that there’s an excellent chance that it’s ground zero for the Next Big One, this may well be as close as we can get to an earthly paradise. All of which is by way of trying to put the controversy surrounding the Drakes Bay Oyster Company, which harvests more than a third of the state’s oysters, in some kind of context.

People have been harvesting oysters commercially in the waters of Drakes Estero, an estuary on the southern edge of the Point Reyes peninsula, for more than a century; President Kennedy signed the bill creating the Point Reyes National Seashore in 1962, and ten years later the government paid the Johnson Oyster Company nearly $80,000 for the property for inclusion in the park, offering the company a forty-year nonrenewable permit to continue operating.

In 1976, Congress passed a law designating the 2,500 acres of tidelands and submerged land of Drakes Estero as a marine wilderness effective upon the termination of that permit. In 2004, the Johnsons sold out to the Lunny family, longtime local cattle ranchers, who continued operating as the Drakes Bay Oyster Company; apparently the Lunnys assumed that the government would let them continue harvesting oysters in the estuary past 2012, even though the government told them that “no new permit will be issued.”

In November 2012, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar formally announced that he was allowing the permit to expire, though various court orders allowed the company to keep operating. Last week, however, a three-judge panel of the Ninth U.S. District Court of Appeals ruled 2-1 that the federal government was within its authority in terminating the permit. The next step is uncertain, though the company will probably seek a hearing before the full court.

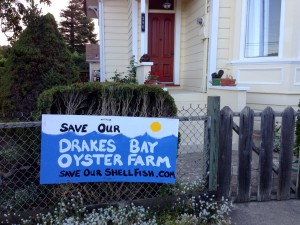

The case has become something of a cause célèbre in normally mellow Marin. While the Interior Department tries to do what’s right from a national perspective, fulfilling a Congressional directive and following the letter of the law, Point Reyes Station and the surrounding rural areas are thick with hand-painted blue-and-white signs begging “Save Our Drakes Bay Oyster Farm”—hardly surprising, I suppose, given the fact that the Lunny family has been here for a century, and the general antipathy toward Big Government among small farmers and ranchers. Supporters of the company have even started a Website, SaveOurShellfish.com, which is full of populist fervor, arguing that the feds “are illegally denying Californians their rights to shellfish cultivation in Drake’s [sic] Estero” and urging people to “Join us in standing up for the People’s right to this remarkable food source!”

The company’s own Website makes much of the Lunnys’ commitment to environmentally sound practices. Its mission statement reads, in part, “All of our growing, post harvest and delivery practices are built around sound and sustainable agricultural practices with ecological responsibility and a long-standing attitude of stewardship for the land and sea that we farm.” A number of local restaurants and farm bureaus have weighed in on the company’s side. The legendary Alice Waters of Chez Panisse noted the importance of “a community of scores of local farmers and ranchers, such as the Lunnys, whose dedication to sustainable aquaculture and agriculture assures the restaurant a steady supply of fresh and pure ingredients.”

Meanwhile, critics of the Lunnys argue that they have not always lived up to their lofty claims. The California Coastal Commission charged the company with “illegal coastal development, violation of harbor seal protection measures, and failure to control significant amounts of its plastic pollution.” Various environmental groups have arrayed themselves on the government’s side. Neal Desai of the National Parks Conservation Association said that the decision “affirms that our national parks will be safe from privatization schemes, and that special places like Drakes Estero will rise above attempts to hijack America’s wilderness.” A Huffington Post story noted that the Washington nonprofit providing the company with pro bono legal representation had ties to the arch-conservative Koch brothers and was a front for the nationwide effort to open public lands to private exploitation.

It is impossible for an outsider like me to know what to make of all this; the controversy quickly becomes a morass of he said, she said charges and countercharges. Without knowing the details of the situation or the principals involved it is impossible to tell where the objective truth lies, if there is such a thing—which is, I grant you, a pretty big if. It seems, however, that each side has come to believe the worst about the other.

When I was a kid growing up in Mill Valley, Marin County was a byword for a laid-back lifestyle. Beads, patchouli, incense, peacock feathers, and—I admit it—large quantities of high-quality dope were part of the equation, as was one of the highest per-capita incomes in the country, and while it has always been easy to make fun of “Mellow Marin” (see Cyra McFadden’s The Serial: A Year in the Life of Marin County, for example), many people here seem genuinely committed to living in gentle harmony with each other and with Mother Nature.

Mark Dowie is an environmental journalist who lives on the western shore of Tomales Bay. In the latest issue of the West Marin Review, he writes: “I remain an environmentalist. I believe we all are at heart. But I’m a hybrid, a fence-sitter, observed with caution by ranchers and Greens alike. I’ve lost a few friends on both sides of that fence.”

He adds, “The science of land stewardship is still unfolding and it’s hard to know what’s right. But it seems clear that one right thing is communication. Close, patient, and honest dialogue between ranchers and enviros will make great strides toward right-stewardship and toward consensus in the land disputes that plague the West. Those conversations are often best had around kitchen tables.”

Given the apparent intransigence, suspicion, and bitterness on both sides, the opponents in this controversy aren’t close to sitting down at the kitchen table together; hell, they’re not even in the same building, figuratively. (Literally, it’s a different story: a block from the house we rented is a 114-year-old former livery stable with one of those blue-and-white “Save Our Drakes Bay Oyster Farm” signs on the wall facing Third Street, and in that building is the office of the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin, which supports the decision to close the company down.)

Perhaps I’m being childish, but I can’t help wishing, with Dowie, that the locavores and the environmentalists could find common ground. This is a special and beautiful place, and it shouldn’t be that hard to agree on the need to keep it that way. But right now “Mellow Marin” seems a little less mellow, a little more like the rest of the world, and that’s a shame.

What we’re reading

Heather: Andrea Barrett, Servants of the Map

Martin: Edmund de Waal, The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance

Your story is well written, Martin, and I agree it is very sad to hear the two sides have come to this level of intransigence. I wrote my university honours thesis on the amazing story of how Point Reyes came to be a national park and then part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. What made this story so unique was the collaboration, and indeed communication, that was necessary between ranchers and conservationists, and, back then, the development interests of the Park Service. It was also one of the first times extensive public consultation was used to design a park, and once the hours and hours of surveys and meetings were conducted, the consensus was that what people most loved about visiting Point Reyes was seeing the rural lifestyle with cattle ranches and the rugged farmsteads mixed alongside the wild landscape with amazing forests and coastline. Most people did not want to see holiday homes and hotels, which is what the Park Service and other development interests of the day had in mind.

Fortunately at that time we had the amazing foresight and leadership of several congresspeople and numerous local heroes who fought hard for a consensus that preserved the Point Reyes that we have all had the benefit of enjoying for the last few decades. (See Harold Gilliam’s Island in Time for one account of the Point Reyes story.) I certainly hope the vision of the original park founders and the work they did to create such a unique living landscape is not forgotten in the rancorous debate currently underway.